Originally published in Tarde

▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒

This issue was prepared by Tomás Criado and curated by Ester Gisbert Alemany. Design and edition: Santiago Orrego.

▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒▒

Editorial note: Landscaping Pavements is the first issue in a series of urban explorations that are part of an ongoing collaboration between Tarde and xcol.org.

We, modernist urbanites, tend to have a very strange relation to the streets we tread on as if walking was an act of material oblivion. Indeed, every step seems to push us further away from them instead of bringing us closer to the ground. It’s as if the pavements we walk on permanently disappeared from view: their silent permanence, stubborn smoothness, and standardized sturdiness becoming almost unthinkable. As if they were just there, supporting without mattering much, as well-ordered stages of public life, quintessential furniture of liberal ideas of politics: our contemporary agora! [1] So much so that only children dare to ask: who has laid the streets overnight for us to walk on them?

The streets and the sidewalks, as we know them, need to be conceived, invented, and installed, and they are permanently under maintenance. Hence, pavements, not just pedestrians, also deserve a genealogy! [2] In fact, they bear in them the imprint of the clean slate of progress and modernity: from their durable materials – tarmac or granite, you name it – extracted from the belly of the Earth to their bulldozed modes of construction as perfectly sealed soils [3]. This is their secret engine, the unrevealed truth, the machinery they conceal, so we don’t think much of them.

Even if there have been many traditions of incredible technical prowess, creating walkable roads and ways across the globe – The Great Wall of China! The Andean Qhapac Ñan! – paved streets stand out as a peculiarly modernist infrastructure: the result of early Modern zonification to prevent killings from horse and chariot transit, subject to subsequent endless policing and reforms for the sake of hygiene and decorum. Later on paving, literally, the way for automotion to take the world as a hostage [4].

Their construction has brought about the modern city as we know it and has also partaken in assembling its quintessential walkers: from the need to wear shoes to the compacted ground on which we walk. So much so that the beloved flâneur of Walter Benjamin cannot be thought of but as an infrastructural being, the result of Hausmann’s spatial reordering: nature below, what only experts can access to, culture above, for us to window-shop into eternity [5]. The academic and political centrality of a white, able-bodied male figure standing out for the profound oblivion of the material world that bore its creation is also a symbol of many things that cannot go on, damn urban studies!

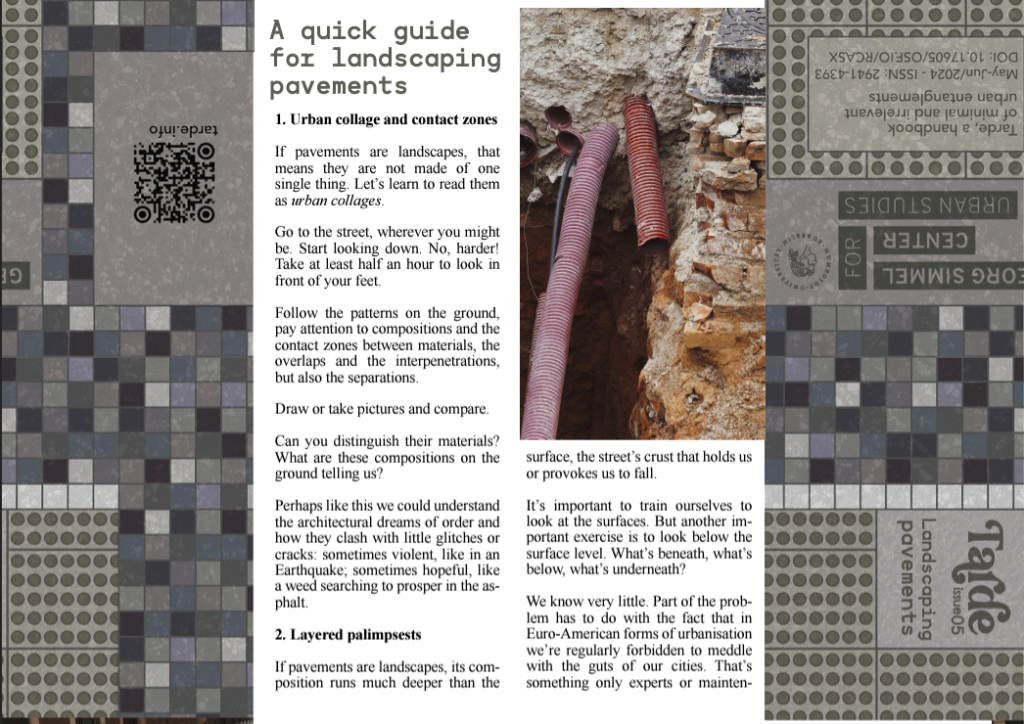

In the meantime, Euro-American urbanists seem to have been captured with what Gordon Cullen called ‘townscapes’: a rather peculiar form of landscape design promising visual coherence, orderliness, and organization of “the jumble of buildings, streets, and space that make up the urban environment”[6]. The frenzy of late 19th-century urban modernization laid the grounds for pavements to become everyday, more highly technical endeavors. This is the marvelous tale historian of art Danae Esparza recounted in her incredible book Barcelona a ras de suelo (Barcelona at ground level)[7]: a detailed exploration of the perpetual redesign that the city’s pavements have undergone since the Romans. One of the most salient features being the devoted efforts in the last one hundred years to engineer their durable and stable foundations – compacting the soil, layering insulation materials like aggregate – together with patterning the outer crust, its walkability and grip, in attempts at rendering urban space readable: a legible milieu? Nothing represents this better than the Panot Gaudí, “the hexagonal hydraulic tile he [architect Antoni Gaudí] designed in 1904 in conjunction with Escofet”[8]. As a result of the work of the municipality, together with corporations that have specialized in designing ‘urban elements,’ pavements have become part of a system: one more element of a catalog of products by which a deeply modernist city is perpetually made and remade into a static image of itself, a collage of ready-made building types, their additions and subtractions.

The tensions that these demands generate were apparent in a rare gem of an exhibition, titled Debaixo dos nossos pés (Under our feet)[9], which opened Lisbon’s inner guts to foreground a multi-layered display of pavements from the times of its first inhabitants to the present. The exhibition happened at a time of increasing pressures for urban standardization, not just having city branding at their core but also concerns for accessibility, desperately demanded by disabled and older people for decades. The strange lure and aestheticization of an urban image can also happen at the expense of traditional forms of street-making, pushing aside those who manipulate them. This has become evident in public struggles to keep their early modern ‘traditional’ configuration (calçada portuguesa, a peculiar form of cobblestone-based pattern) and the communities of practice of their soon-to-be-extinct trade (calceteiros), unless turned into World Heritage, a paradoxical fixation to resist a more contemporary fixity?

Ecologically speaking, this fixation is also highly problematic. In his signature process-oriented anthropology, which attends to the dynamic processes of sentient beings’ world-formation, Tim Ingold takes issue with the modernist practice of hard surfacing the earth because it “actually blocks the very intermingling of substances with the medium that is essential to life, growth, and inhabitation”[10].

This is far from being a cumbersome theoretical issue: the European Environmental Agency has been alerting for years of the many problems that sealed soils are bringing to the fore– related to heat island effects and underground degradation –particularly in urban settings[11]. As a consequence, environmentally-minded architects and urban planners have started to uncover ‘the beach beneath the street’: depaving the streets or creating porous sidewalk materials to foster the important underground soil relations essential to life on Earth[12].

Far from being the dirt beneath our shoes, in geography, anthropology, and environmental humanities, the very soils we used to tread on are increasingly becoming a matter of relational engendering with different beings, animating newer forms of social theory and eco-political practice[13]. The world beneath our feet, hence, appears before us as a moving territory with its own history, formed – or even ‘terraformed’ – by a wide variety of beings, from worms and plants to different animals and human groups.

Perhaps there would be no better way to re-enliven pavements and their politics than to treat them as landscapes in their own right. Not in the early modern sense of the term – used in geography and other cognate disciplines to fixate stable nature-cultural patterns[14] – or in the same sense that still breathes in the notion of townscape mentioned before, but in a new materialist sense: thinking from their complex temporal and spatial material interconnectedness and their ongoing, engendering process[15]. All of a sudden, the streets we walk cease being the same. What appeared static, indeed, moves! Pavements are, indeed, terraformed. This can happen in strange and imperceptible ways as part of the earthly transformation of microbiota or weeds. However, pavements are also ‘being moved’ due to violent capitalist extraction, as it happens in the far-away travels of many of the anonymous materials that constitute the world at our feet, captured landscapes whose origins remain obscure[16].

Holding these two forms of terraformation in tension, treating pavements as landscapes – put otherwise, ‘landscaping’ pavements – might be a way for them to start speaking back. Not as the mute foundations of the present but in their strange temporal mash-ups: between deep and shallow time. Manuel de Landa provides an apt metaphor for this approach to city-making: “About 8000 years ago, human populations began mineralizing … when they developed an urban exoskeleton, bricks of sun-dried clay became building materials, stone monuments, and defensive walls”[17]. A good example of this mineralization, a peculiar form of landscaping pavements, is the city of Rome. But not the classic and boring take that obsessed many neoclassic and fascist architects and artists. I’m thinking here of the fantastic visualizations landscape architect Kristi Cheramie has worked hard to unearth: in them, Rome appears formed as a concatenation of acts of landscaping. The contemporary city is deeply entrenched in the terraformation that the ancient one undertook. A geological entity whose complex boundaries are also those of the very Mediterranean olive oil trade, sedimenting a way of living as well as the mode of circulation that saw its growth and demise [18]. Landscaping pavements enable us to study and dimension the agents involved, their temporal and spatial effects, their material configurations, and their acts of becoming with them [19]. Thus understood, our urban arenas appear as layered compounds, ongoing palimpsests through and through [20]. Conceived in this way, the city, as Francesc Perers calls it in a rather peculiar photo-book on Barcelona’s sidewalk archaeology, turns into “a cohabitation of strata”[21].

How could we begin to exercise this landscaping approach when we walk?[22] What exercises could we engage to reconnect to and partake in these underground palimpsests that are also our very mineral and multispecies condition? How do we liberate pavements and inhabit closer to them, entering into newer urban formations?[23]

The exercises proposed in this issue wish to propose concrete avenues for this to happen. Following them, perhaps the next time you walk into the streets, walking might just be the beginning of a passionate conversation at the tip of your feet:

What could you tell me, oh, anonymous piece of stone?

From what quarry do you come from? Who took you from the belly of the Earth? Who broke and dismembered you from the common body of other stones, using what machine? What standard shaped you? How might others resist the corset you provide? How will you let me walk on you when it rains?

Oh, you macadam, strange collective body, interconnected and singular, strangely one, what life can you also give? How have you been prepared for me to tread you, using what procedures? Under what technical or parliamentary regulations? How could you resist this encounter?

Oh, you all strange pavements: What life do you also partake of? What new city could we engender, together with the others who could crack you, and make you into their new home?

Online references

[1] Loukaitou-Sideris, A., & Ehrenfeucht, R. (2011). Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation over Public Space. MIT.

[2] Blomley, N. (2011). Rights of Passage: Sidewalks and the Regulation of Public Flow. Routledge.

[3] Ammon, F. (2016). Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape. Yale University Press.

[4] Norton, P. D. (2008). Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. MIT.

[5] Meulemans, G. (2017). The Lure of Pedogenesis: An Anthropological Foray into Making Urban Soils in Contemporary France. PhD in Anthropology, University of Aberdeen; Domínguez Rubio, F., & Fogué, U. (2013). Technifying Public Space and Publicizing Infrastructures: Exploring New Urban Political Ecologies through the Square of General Vara del Rey. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), 1035–1052.

[6] Cullen, G. (1961). The Concise Townscape. Routledge.

[7] Esparza, D. (2017). Barcelona a ras de suelo. Universitat de Barcelona Edicions.

[8] See https://www.escofet.com/en/blog/true-story-gaudis-panot

[9] Bugalhão, J., Fernandes, L. & Fernandes, P.A. (2017). Debaixo dos Nossos Pés. Pavimentos históricos de Lisboa. Museu de Lisboa.

[10] Ingold, T. (2011: 124). Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Routledge.

[11] See https://www.eea.europa.eu/articles/urban-soil-sealing-in-europe

[12] Núñez Rodríguez, M. (2015). ¡Bajo el asfalto, los adoquines! Proyecto de investigación sobre los servicios ecosistémicos de distintos pavimentos. Ayuntamiento de Madrid, https://mmmapa.com/portfolio/bajo-el-asfalto-los-adoquines-proyecto-de-investigacion-sobre-los-servicios-ecosistemicos-de-distintos-pavimentos; Baraniuk, C. (23rd February 2024) The cities stripping out concrete for earth and plants. BBC, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240222-depaving-the-cities-replacing-concrete-with-earth-and-plants; BitHabitat (2022) https://bithabitat.barcelona/projectes/el-panot-del-segle-xxi

[13] Salazar, J. F., Granjou, C., Kearnes, M., Krzywoszynska, A. & Tironi, M. (Eds). (2020). Thinking with Soils: Material Politics and Social Theory. Bloomsbury.

[14] Wylie, J. (2007). Landscape. Routledge.

[15] Seibert, M. (Ed.). (2021). Atlas of material worlds: Mapping the agency of matter for a new landscape practice. Routledge; Harkness, R. (2017). An Unfinished Compendium of Materials. University of Aberdeen.

[16] Cronon, W. (1992) Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. W.W. Norton and Co.; Hutton, J. (2020). Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements. Routledge.

[17] de Landa, M. (1997: 26-27). A Thousand Years of Non-Linear History. Zone Books.

[18] Cheramie, K. (2020). Through Time and the City: Notes on Rome. Routledge.

[19] Gisbert Alemany, E. (2022). To do a landscape: Variations of the Costa Blanca. PhD in Architecture. University of Alicante

[20] Mattern, S. (2017). Code and Clay, Data and Dirt: Five Thousand Years of Urban Media. University of Minnesota Press; for a challenging example, see the Ghost Rivers “public art project & walking tour, rediscovering hidden streams and histories that run beneath our feet”: https://ghostrivers.com/

[21] Perers, F. (2017: 131) Voreres. La memòria subtil. Ajuntament de Barcelona.

[22] Mattern, S. (2013). Infrastructural Tourism: From the Interstate to the Internet. Places. https://placesjournal.org/article/infrastructural-tourism/; Kanouse, S. (2015). Critical Day Trips: Tourism and Land-Based Practice. In E. E. Scott & K. Swenson (2015). Critical landscapes: Art, space, politics (pp. 43-56). University of California Press; Shepherd, N., & Ernsten, C. (2021). An Anthropocene journey. In H. S. Rogers, M. K. Halpern, K. D. Ridder-Vignone, & D. Hannah, Routledge Handbook of Art, Science, and Technology Studies (pp. 563–576). Routledge.

[23] Duperrex, M. (2022). La rivière et le bulldozer. Premier Parallèle.

***

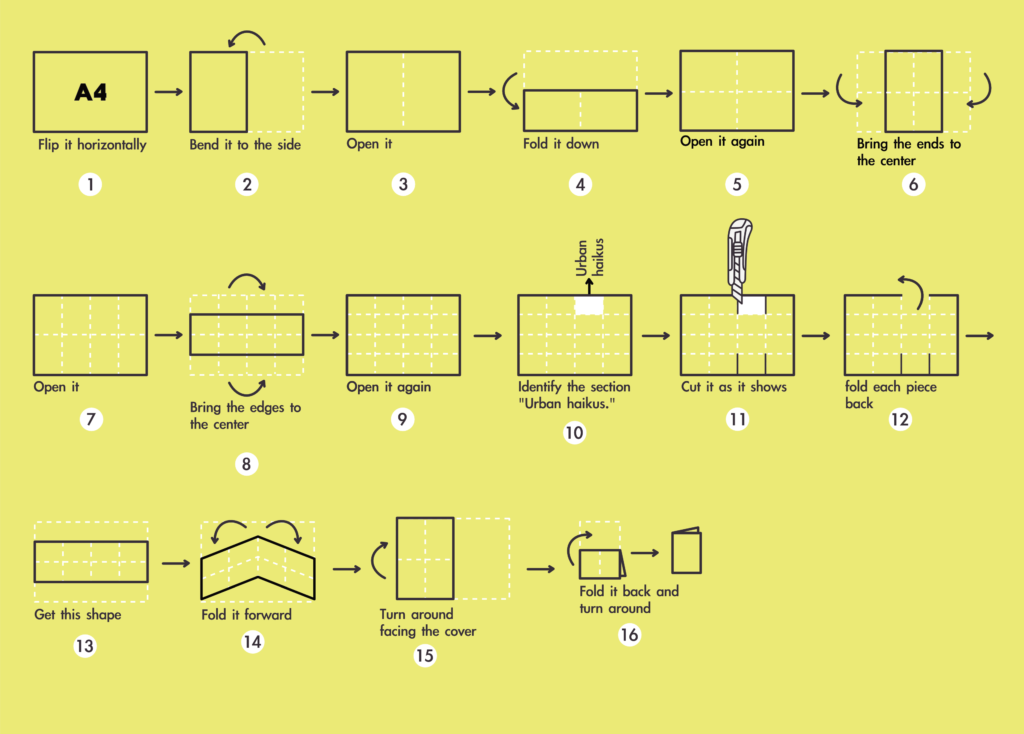

This number experiments with a different folding format. Although it starts with an A4 piece of paper and keeps the original A7 form when it is folded, the process of assembling it changes dramatically. The most notorious of those changes is the design of a small foldable gallery by taking advantage of different paper cuts.

Recommended citation: Criado, T.S. (2024). Landscaping Pavements. Tarde, a handbook of minimal and irrellevant urban entanglements, 5. DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/RCASX