Presentación del taller La ciudad de las sombras: Etnografiar la habitabilidad urbana en tiempos de mutación climática (17-21 de junio de 2024 | Barcelona)

Nuestra cultura climática está en crisis. El calor extremo ya no es un evento externo, está entre nosotros, como un mal crónico con profundos efectos desiguales y devastadores.[1]

De manera peculiar para un país como el nuestro, acostumbrado al sol y al calor como un asunto estacional recurrente, esto nos sitúa ante una crisis en la que podemos creernos sobre-preparados. Pero verano tras verano, ola de calor tras ola de calor, los hábitos y prácticas heredados no acaban de funcionar: ya no basta con caminar a cubierto, llevar crema solar, beber mucho, vestirse ligero, bajar las persianas y esperar a que pase lo peor, porque lo peor está por llegar, en esas noches tórridas, tropicales e infernales, como las llaman nuestras colegas de la meteorología.

Las infraestructuras y modos de construcción modernos, que nos hacían sentir a la vanguardia, aparecen hoy irremediablemente problemáticos. Necesitamos un cambio radical. Diferentes organizaciones internacionales e intergubernamentales alertan desde hace tiempo que la respuesta al cambio climático debe partir de las ciudades:[2] asentamientos cada vez más poblados e infraestructuras complejas de cambiar desde los que necesitamos repensar la habitabilidad del planeta.

La mutación climática en curso nos sitúa ante el reto de configurar nuevas ideas urbanas de cuidado, protección o refugio, inventando formas plurales de habitar que protejan a quienes pudieran estar más expuestos o sufrir más sus efectos devastadores.[3] En ese sentido, vivimos un tiempo de urgencia y de búsqueda frenética de soluciones. Sin embargo, y ésta es mi propuesta, además de soluciones infraestructurales o “basadas en la naturaleza” tenemos ante nosotros una tarea importante: esto requiere, sobre todo, redescribir qué es lo urbano.

En situaciones de gran incertidumbre, donde cómo responder es un asunto a veces complicado de imaginar, quizá necesitemos entrenarnos a prestar atención a lo aparentemente irrelevante, pero crucial. Ese es el objeto primordial de este taller, que quiere poner el foco en las sombras: entidades aparentemente ínfimas, pero que articulan nuestra vida urbana y nuestras relaciones cotidianas con el sol y el calor.

Sin duda, no hay nada más convencional que la sombra. En tanto seres terráqueos todos tenemos una. Pero pensar la sombra urbana puede ser algo mucho más profundo de lo que parece, puesto que nos obliga a prestar atención de otra manera a nuestros entornos cotidianos. De hecho, ¿qué es la sombra, sino una relación cambiante en que entramos con el sol a medida que atraviesa nuestros hábitats a lo largo del día?

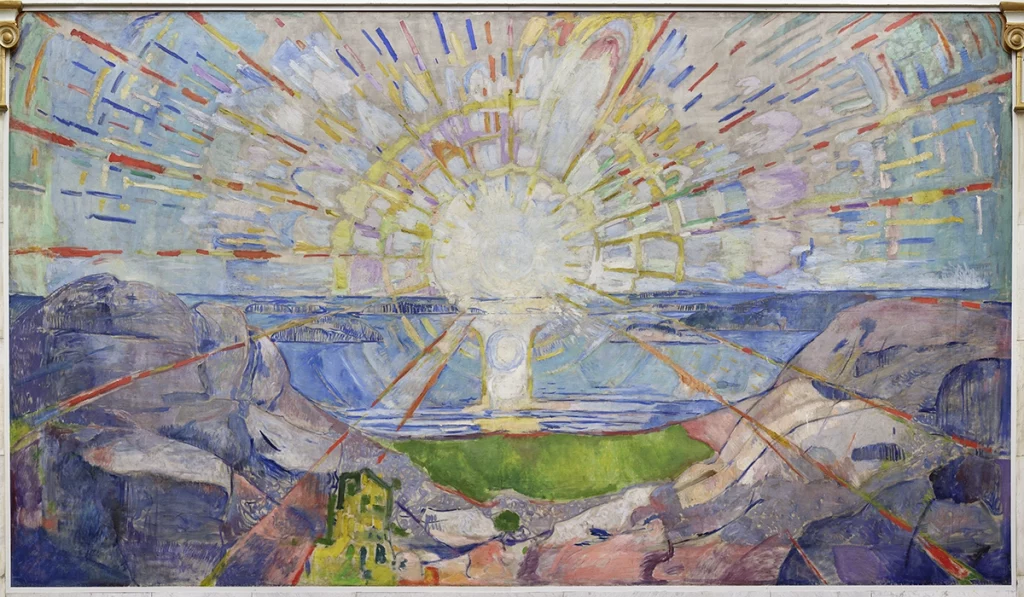

Con Copérnico y Galileo, la modernidad puso al Sol en el centro. Uno de los muchos efectos de ese giro heliocéntrico y su profunda transformación cosmológica es que solemos atribuir a la estrella que preside nuestro firmamento un rol benefactor, la capacidad de dar vida y de irradiarnos con su fuerza, pero esta apreciación regularmente positiva necesita un contrapunto: ¿qué hacer cuando nos daña o nos pone en riesgo, como en las condiciones atmosféricas del calor extremo o en la exposición solar que conduce al melanoma?[4]

La tradición filosófica moderna, pero también nuestras formas de expresión artística y folklore (con innumerables canciones infantiles alabando al sol), tiene dificultades para no tratar con prejuicio todo lo que queda por fuera de esas irradiaciones: una caricatura solarizada, tratada como lo arcaico, lo conservador, lo peligroso, lo turbio de la noche. Sin embargo, y esta es la hipótesis que quisiera compartir aquí, ¿y si nunca fuimos solares? ¿Y si para volver a respirar y pensar, guarecidos de su poder salvaje, a la sombra, necesitemos desplazar al sol del centro?

Esto no necesariamente quiere decir dejar de considerar al sol, ni resucitar la desconfianza platónica que nos condena a no ver más que las sombras proyectadas en las paredes de una cueva. El tipo de pensamiento cobijado que pudiéramos empezar a practicar tiene, más bien, en su centro a la sombra: ¿Y si la sombra no fuera la posibilidad de pensar en negativo, tomando las cosas por lo que no son, sino un modo de pensar protegido del sol abrasador? De hecho, como mostró ampliamente la pintura barroca, las sombras son centrales para nuestra percepción, para nuestro entendimiento del mundo, para nuestra supervivencia. [5]

Con esa clave, nuestra vida terrestre pudiera ser leída como una larga historia interespecífica de cómo los vivientes hemos aprendido a protegernos de su irradiación. Ese es uno de los argumentos más interesantes del trabajo del paleontólogo y geólogo Anthony J. Martin Evolution underground (la evolución bajo tierra), que retraza la importancia evolutiva de las madrigueras y arquitecturas del subsuelo para la supervivencia sobre la faz de la tierra de muchos animales desde tiempos inmemoriales, incluidos los seres humanos.[6]

Pero, yendo más allá, la misma atmósfera, logro inicial bacteriano, con su compleja circulación del aire, o más tarde en la historia de la tierra los mares y las riberas de los ríos o el tapiz irisado de las nubes y los bosques no son sino un gran sistema, con expresiones locales, de formas de captar, regular, disipar o bloquear los rayos del sol. En esta centralidad de la sombra no podemos olvidar a las plantas y su importante papel en hacer habitable nuestro planeta.

El filósofo Emanuele Coccia expresaba esto de forma muy poética en una reciente conferencia en el CENDEAC, titulada “El jardín del mundo”. En ella planteaba que lo que hoy llamamos Tierra no puede entenderse sino como consecución técnica de la vida o la labor de las plantas, cruciales para la producción de la atmósfera y la orografía, así como del oxígeno gracias al cual otros seres vivimos:

“la Tierra tiene un estatuto de artefacto… una producción cultural de todos los seres vivos que lo habitan y no sólo la precondición trascendental para la posibilidad de la vida. Gaia es hija de Flora. El sol es la muñeca cósmica de Flora.”[7]

¿Y qué hubiera sido de la terraformación de nuestro planeta a través de las plantas y, en particular los árboles, de no ser por su capacidad de transformar lo, producir hábitats o microclimas para que muchos animales pudiéramos comenzar a reptar más allá de los mares, cobijados del sol?[8]

De hecho, muchas de nuestras experiencias primordiales de sombra y protección del sol tienen que ver, de hecho, con los delicados entramados del follaje de distintos árboles y plantas. Pensar junto con los árboles nos permite aventurar otra hipótesis sobre la habitabilidad de nuestro planeta: ¿Y si la sombra fuera más importante de lo que nos hemos contado hasta ahora? Es más, a pesar de que suela ser considerada como un producto secundario del sol, su versión en negativo, ¿y si la sombra fuera condición misma de la habitabilidad en la tierra y, por ende, en nuestros entornos urbanos atribulados por la mutación climática?

Lo interesante es que, aunque la sombra sea una vieja conocida, la creciente preocupación ambiental ha hecho que administraciones y profesionales de todo tipo hayan comenzado a recuperar esta relación ambiental cotidiana largamente olvidada por las formas modernas de urbanización. Por esto mismo ha cobrado gran importancia en distintas soluciones técnicas para hacer frente al calor extremo del presente: planes municipales de sombras, itinerarios bioclimáticos o infraestructuras de sombreado.[9] Esto está requiriendo revitalizar saberes y técnicas antiguos, así como especular y crear nuevas soluciones para mitigar y adaptarnos ante el calor creciente.

Decir que no hemos sido solares, prestar atención a las sombras, significa también restaurar la violencia ejercida contra muchas tradiciones ancestrales del habitar por parte de los modernos, con su obsesión higienista por el aire limpio y las calles amplias, controladas y destinadas primordialmente al tránsito. Este urbanismo heliocéntrico fue la forma en que la Razón se hizo ciudad. Frente a ello, colocar la sombra en el centro es restituir su centralidad para la habitabilidad urbana, lo que nos permite admirar con otros ojos a la mal llamada arquitectura vernácula: buscando inspiración.

Sin embargo, decir que nunca hemos sido solares no es tirar la arquitectura modernista por la borda, sino comenzar a advertir formaciones urbanas modernistas para las que la sombra ha sido nuclear. Esto es, se trata de releer la arquitectura y el urbanismo no desde la luz, sino desde la centralidad de la sombra, como plantea el arquitecto Stephen Kite en su libro Shadow-makers, una historia cultural de las sombras como factor modelador de la arquitectura (“shaping factor in architecture”), tanto en las formas tradicionales como modernas.[10]

Aunque gran parte del libro de Kite está consagrado a la importancia de la sombra para definir las oquedades de edificios y espacios interiores, hay un capítulo maravilloso sobre la ciudad islámica mediterránea y de Oriente Próximo, porque ¿qué es la medina –– conglomerado formado por arquitecturas de adobe de cañón largo y usos de toldos o tejidos humedecidos –– sino una gran oda a la sombra como principio de habitabilidad urbana?[11]

Pero existen también ejemplos interesantes de tratamientos urbanos de la sombra en diferentes tradiciones modernistas que se han desarrollado en climas cálidos y áridos, de lo que trata ampliamente una reciente exposición sobre el modernismo tropical en África y la India comisariada por Christopher Turner en el Victoria and Albert Museum de Londres.[12]

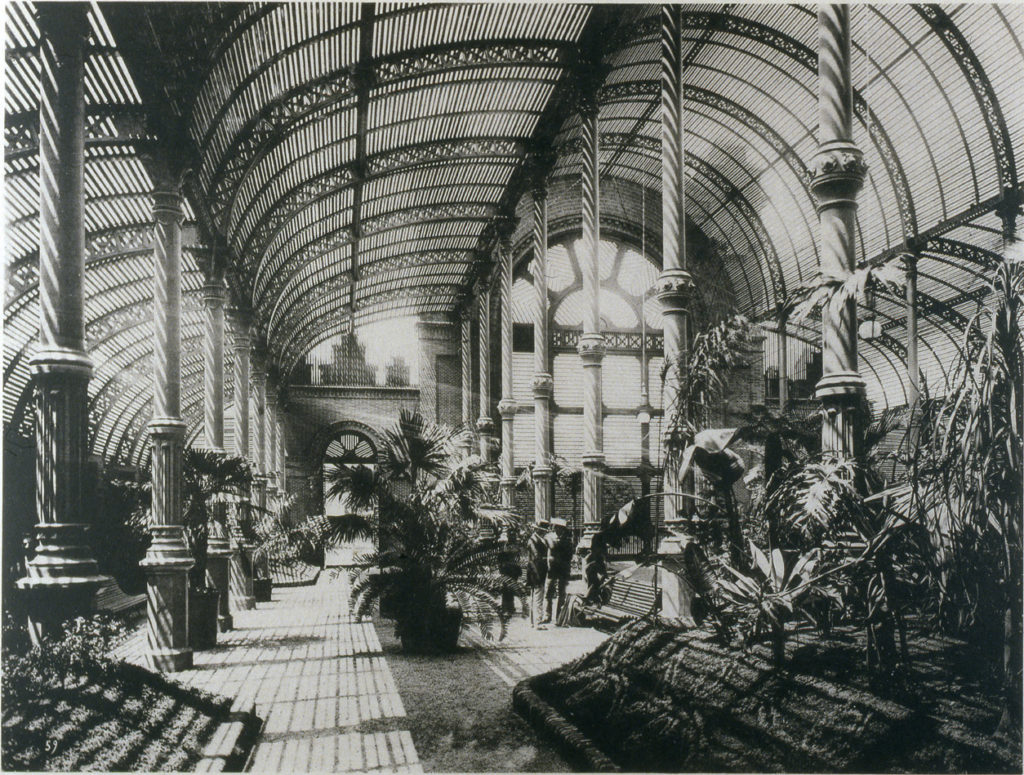

En Barcelona hay también una historia por reconstruir de las arquitecturas modernistas de la sombra, de entre las que destacan los dos umbráculos de los parques de la Ciutadella y Montjuic: estructuras siamesas, pero que funcionan por el principio inverso al invernadero; concebidas como parte del mismo impulso tenebroso que la historiadora de la arquitectura Lydia Kallipoliti denomina las gramáticas de la “aclimatización colonial”, que permitieron el frágil transporte o la relocalización masiva de plantas, animales y personas, para su comercio y exposición, en ocasiones comenzando una nueva vida problemática en el corazón de la metrópolis.[13]

Y, sin embargo, las soluciones del pasado, por problemáticas o interesantes que resulten, no puede ser la solución. Hemos entrado en un momento experimental, de gran estupor. Nuestras ciudades se han convertido en lo que el filósofo y antropólogo francés Bruno Latour llama “zonas críticas”: complejos territorios ignotos, donde los vivientes se están jugando la vida literalmente, pero también donde más se apresuran para seguir haciendo mundos vivibles, en su pluralidad irreductible.[14] El reto ante el que nos sitúa lo que Latour llama el “nuevo régimen climático” en estas zonas críticas urbanas es, por tanto, engendrar formas plurales de habitabilidad en un momento francamente complejo y problemático, sin garantías.[15]

Para responder tentativamente a este reto mayúsculo creo que necesitamos practicar una cultura experimental de la transformación urbana. Esto puede sonar paradójico, lo sé, porque estamos en un momento en el que sentimos que debemos correr para hacer algo. Pero debemos tener cuidado de no convertir esta prisa en un proyecto tecnocrático gobernado por expertos o por élites que le digan o le impongan al resto cómo vivir, como ya ocurrió en el periodo colonial. Si la vida es compleja, si la vida consiste en fabricar las condiciones generativas de hacer la tierra habitable, podemos sin duda advertir que están pasando cosas ciertamente tenebrosas, pero existe un gran peligro de confundir el diagnóstico con la solución, sobre todo cuando no sabemos cómo podremos vivir y con quién.

Precisamente en ese momento de urgencia, necesitamos más que nunca una cultura experimental para repensar la ciudad. Con esta prevención de la solución técnica no quiero decir que no sean importantes innumerables arreglos infraestructurales como pavimentos porosos y reflectantes, espacios de sombra para protegernos del sol de justicia y del efecto isla de calor, o dejar sitio para que la vegetación autóctona se desarrolle o que los animales vuelvan a ocupar un lugar central en las ciudades. Sin lugar a dudas todo esto es central, pero necesitamos ir más allá.

En un momento así, necesitamos también abordar la vida social y cultural de muchos fenómenos atmosféricos y climáticos, como las sombras, sean estas ya existentes o diseñadas. En un presente acalorado, donde la capacidad de cobijarnos del sol abrasador es un bien mal repartido, revitalizar sus saberes y prácticas generativas quizá sea crucial para reaprender a vivir como seres terráqueos. Para ello, quizá necesitemos, un ‘Departamento de Umbrología’ en cada uno de nuestros territorios.

Este idea está inspirada en una propuesta desarrollada por el escritor Tim Horvath en su cuento corto The discipline of shadows, donde explora las complejas relaciones en un absurdo departamento universitario dedicado al estudio de la vida de las sombras, donde coexisten sin entenderse y generando muchas situaciones cómicas y de incomprensión supina físicos, dramaturgas del teatro de las sombras y filósofos platónicos.[16]

Sin embargo, en un momento absurdo como en el que nos encontramos, el taller es una invitación a co-crear y explorar cómo hacer existir un tipo de espacio inspirado por ese cuento, pero no como un departamento universitario. Más bien, tomando inspiración del trabajo de descripción e intervención artivista de colectivos como Los Angeles Urban Rangers[17] o los experimentos especulativos del Gabinete de Crisis de Ficciones Políticas,[18] quisiéramos imaginar un espacio de trabajo entregado al estudio de y la intervención en la vida urbana de las sombras: una umbrología que atienda tanto a los aspectos físicos y materiales como a las relaciones sociales y culturales.

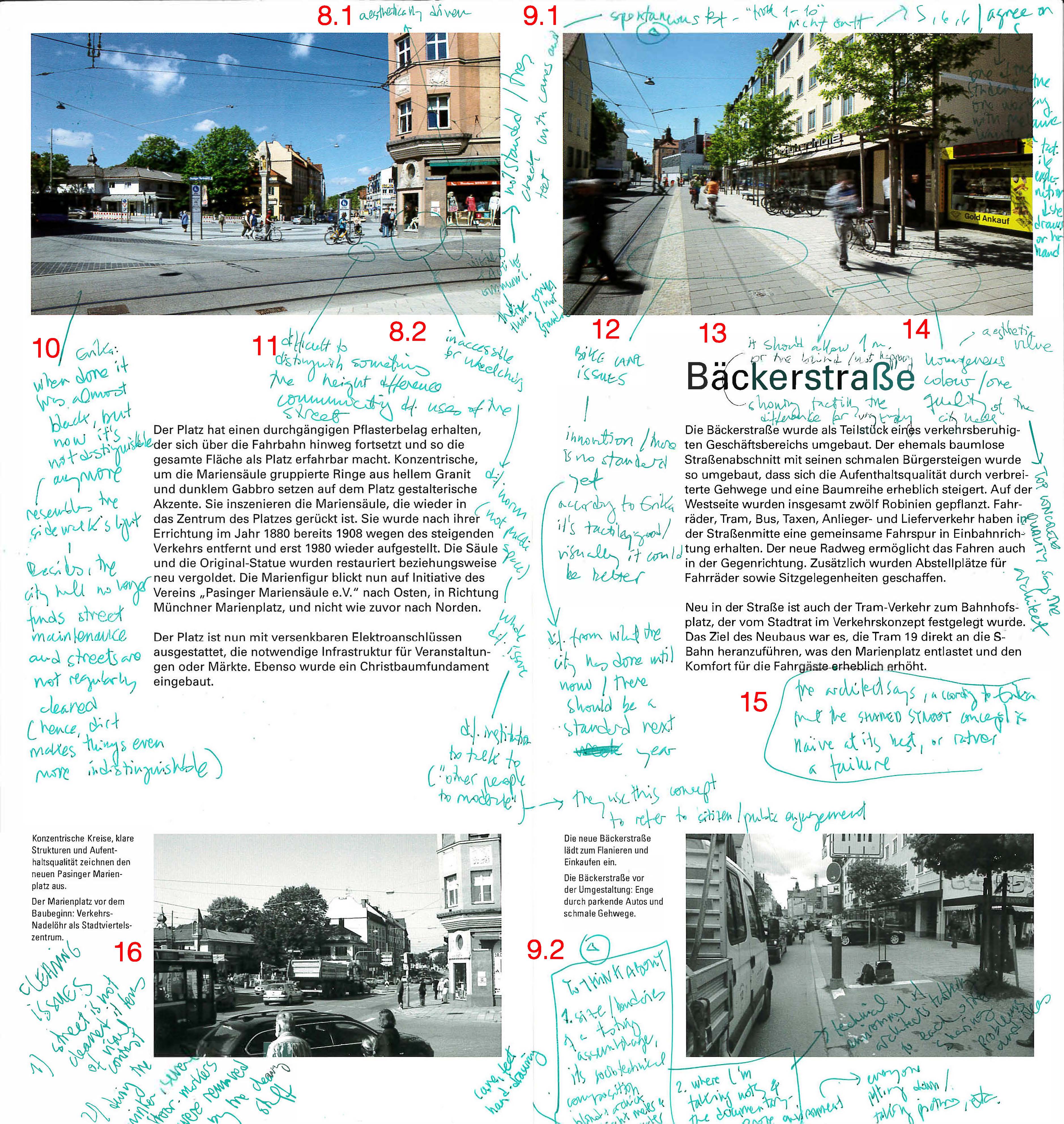

Para hacerlo existir, a través de distintas actividades queremos entrenarnos a apreciar esta relación ambiental: dedicándonos al estudio etnográfico de las complejas relaciones entre el sol y los edificios, la calle o los árboles, así como el papel que distintos tipos de sombras pueden tener para distintas personas o colectivos y sus modos de sobrevivir al calor abrasador. Apelamos a la centralidad de la etnografía, como forma de indagar por la importancia que otorga al estudio de las prácticas, la sensorialidad y los modos de vida, porque creemos que necesitamos comenzar a entender estos fenómenos ambientales más allá de dos formas convencionales con que solemos hacerlos legibles y discutibles:[19]

- Por un lado, las prácticas climatológicas y meteorológicas que ponen la temperatura y otras variables atmosféricas como la humedad en el centro, dejando en la sombra las dimensiones vividas o culturales, las formas de vida de las que surgen y las que hacen emerger, que permiten o dificultan distintos climas;

- Por otro lado, las prácticas de legibilidad del espacio a vista de pájaro y en términos eucliedeanos, como hacen algunas plataformas digitales como ShadeMap o Shadowmap basadas en sistemas de información geográfica como OpenStreetMap que, a través de la geolocalización, permiten simular en nuestros dispositivos la inclinación del sol y las sombras que proyecta el entorno urbano.

Pero quizá para estudiar cómo volver a hacer habitables nuestras ciudades ante un calor creciente, necesitemos también aprender a describir con muchos más matices, tanto simbólicos como efímeros, atendiendo a otros saberes y formas de articular los problemas la nueva terra ignota en que se han convertido nuestras ciudades: fabricando otras cartografías experimentales que, como en el trabajo de Frédérique Aït-Touati, Alexandra Arènes y Axelle Grégoire Terra Forma, nos permitan traer a la centralidad nuestras implicaciones corporales en los climas urbanos que habitamos y la pluralidad de nuestras formas de habitarlos.[20]

La importancia del cuerpo vivido en la etnografía es central porque nos permite dejar de pensar las atmósferas o el clima y, más concretamente, el calor como res extensa: cosas externas desgajadas de nuestro hacer. Antes bien, como bien argumentan diferentes trabajos recientes en los ámbitos de la historia y los estudios sociales de la ciencia y la tecnología, el clima, las atmósferas y el calor son algo de lo que “participamos en su hacer”, por omisión y comisión, de formas más directas o más distantes, en nuestras prácticas cotidianas, encarnadas y mediadas por diferentes instrumentales técnicos, pero también por los modos en que consumimos y construimos ciudades o, dicho de otra manera, por las prácticas colectivas en las que estamos insertos: nuestra vestimenta, nuestros edificios, nuestros aparatos de aire acondicionado.[21]

Así, la sombra deja de ser un mero efecto natural y adquiere también propiedades culturales relacionales: porque no hay una sombra igual a otra y su singularidad depende de cómo la observemos, practiquemos e interroguemos. Esta sensibilidad me parece importante porque nos ayudaría a repoblar la sombra: no como la presentación en negativo de lo que se ve, algo vacío[22], sino como algo que posibilita y ha posibilitado la vida de muchos colectivos que buscan esconderse de la mirada cegadora de la luz, tanto del sol como del proyecto ilustrado.

La centralidad de la sombra como protectora de otras formas de vida resuena en el trabajo del pensador de la tradición radical negra caribeña Édouard Glissant, que en un contexto que todavía convive con la larga cola del esclavismo, defendió “el derecho a la opacidad” como condición de supervivencia para todas las formas de diferencia.[23] Pero también en el sentido más netamente ambiental del que habla el historiador de la arquitectura y activista de la discapacidad David Gissen.[24] Gissen defiende la necesidad de repensar las formas de urbanización desde muchas formas de vulnerabilidad corporal comúnmente apartadas de la centralidad del urbanismo –– las personas negras, mayores y la infancia, con enfermedades crónicas, diversas funcionales, etc. ––, por los considerables riesgos para la salud que el sol y el calor implican: como la de las personas mayores que sufren en silencio el “aislamiento fatal” de las olas de calor o la de la infinidad de cuerpos negros trabajan en exteriores, expuestos al calor y al sol abrasador.[25] Esto disputaría la centralidad del diseño del espacio público con sol abundante, haciendo crucial la sombra como principio de diseño urbano.

Pensando en los arreglos sociales y materiales de la sombra desde esta diversidad de cuerpos que la necesitan para su sostén cotidiano nos permite pensarla no sólo como “recurso cívico”, sino también como un “índice de desigualdad”: una infraestructura de la habitabilidad urbana central que debiera ser un mandato para los diseñadores urbanos, pero que aparece sometido a diferentes condiciones desiguales de acceso y negociación de la producción espacial, en la regulación de a quién se le permite que produzca o viva en la sombra y cómo, en diferentes contextos. [26]

Por tanto, partiendo de esa sensibilidad antropológica queremos: (i) trabajar en el diseño de pequeños materiales para realizar investigaciones de campo; y (ii) hacer un inventario de prácticas espaciales cotidianas, centrado en la relación que diferentes personas tienen con nuestras perpetuas compañeras como habitantes bajo el sol.[27] Experimentando y especulando con cómo poder hacer realidad diferentes Departamentos de Umbrología –– una confederación de entidades autónomas, singulares y auto-constituidas ––, queremos también liberar, imaginarnos y cultivar nuevas sensibilidades y responsabilidades urbanas sobre cómo hacer nuestras ciudades habitables.

Queremos hacernos responsables de describir, proteger y traer a la luz tenue muchos saberes y formas de inteligencia colectiva subterráneos que necesitan soportes opacos para florecer. Queremos, también, poner en discusión las múltiples necesidades de un gran número de actores singulares muchas veces desplazados de la centralidad urbana: no sólo quienes no pueden pagar la factura del aire acondicionado o quienes necesitan soportes para transformar sus viviendas y espacios de trabajo; hablamos, también, de quienes muchas veces no se contemplan como humanos o se nos aparecen como humanos de segunda, además de una gran cantidad de urbanitas no humanos en los que rara vez pensamos.

Para armar esta propuesta puede ser crucial poner a trabajar conjuntamente muy diferentes saberes, profesionales y colectivos, no sólo académicos ni institucionales, que tenemos la gran suerte de tener en esta sala. Esto nos permitirá, además de imaginar ese departamento que, esperemos, deje de ser una ficción de un cuento, hacer que esto ocurra a través de la generación de un proceso de intercambio mutuo y contaminaciones cruzadas.

Ante este reto, por tanto, necesitamos activamente volver a aprender a describir y dimensionar los problemas ante los que nos encontramos – también los problemas de las soluciones –, para así poder ensayar muchas propuestas para hacer posible la habitabilidad plural de nuestros entornos urbanos. Necesitamos, por tanto, cultivar la especulación urbana: ¡no la inmobiliaria! Me refiero a nuestra capacidad de pensar y repensar las muchas formas posibles que podría tener lo urbano para convertirlo de nuevo en habitable.

Explorando e inventando dispositivos de indagación urbana, bebiendo de sensibilidades y saberes de las artes, las humanidades y las ciencias queremos imaginar cómo equipar esos extraños profesionales de la umbrología, entre lo natural y lo cultural, con un interés particular por el análisis y la política de las sombras. Si tenemos éxito en estos experimentos sobre las formas en que entramos en contacto y describimos los mundos urbanos, haremos aparecer otra ciudad: la ciudad de las sombras, normalmente pasada por alto. Y nos entregaremos a entender su complejidad social, así como la multiplicidad de actores y ensamblajes que la constituyen; las formas de generar sombra, por parte de y para quiénes; así como las formas de socialidad que las sombras permiten como regiones o territorios:[28] atendiendo a sus temporalidades, sus ritmos y sus dramaturgias espaciales.

Ante la mutación climática que cambiará cómo viviremos en las ciudades, queremos, por tanto, contribuir a pensar otras formas posibles de habitabilidad urbana más allá de grandes soluciones de todo propósito y pensadas de forma tecnocrática. Es por ello que nuestra llamada a constituir departamentos de umbrología aparezca como un intento de abrir a reflexión colectiva los modos de respuesta urbana al cambio climático aprendiendo de un gran número de agentes urbanos: incentivando, estimulando y ayudando a sostener sus tejidos de saberes y prácticas en formas que bien pudieran exceder a las responsabilidades de las instituciones. Esa es la tarea de un ‘Departamento de Umbrología’ en nuestros territorios urbanos: salir de las sombras, para estudiar las sombras, trabajando “sobre las sombras, desde las sombras.”[29]

[1] Como lo muestran dos recientes informes de la European Environment Agency: EEA Report No 07/2022: Climate change as a threat to health and well-being in Europe: focus on heat and infectious diseases, https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/climate-change-impacts-on-health; EEA Report No 22/2018: Unequal exposure and unequal impacts: social vulnerability to air pollution, noise and extreme temperatures in Europe, https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/unequal-exposure-and-unequal-impacts

[2] Un buen ejemplo de ello es la centralidad que la cuestión del calor y la respuesta ciudadana tiene en el reciente informe del IPCC de 2022, particularmente su capítulo 6 “Cities, settlements and key infrastructure”, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/; o las iniciativas de la Arsht-Rock Foundation formando y articulando “heat officers” en diferentes ciudades: https://onebillionresilient.org/project/chief-heat-officers/ o planteando nuevas formas de preparación ante los riesgos de las olas de calor, categorizándolas o nombrándolas: https://onebillionresilient.org/project/categorizing-and-naming-heat-waves/

[3] Mi argumento bebe y se inspira profundamente en la obra del recientemente fallecido filósofo y antropólogo francés Bruno Latour y muchos de sus colaboradores. En su trabajo de la última década hay una noción central: “Nuevo Régimen Climático”, que remite a los problemas a los que nos ha arrojado un modo de vida particular, la producción y su dependencia de las energías fósiles. Un régimen destructivo que ha transformado nuestros entornos, moldeado nuestros saberes e instituciones políticas durante más de un siglo, poniendo en riesgo la habitabilidad del planeta. Al mismo tiempo, esta caracterización sugiere la posibilidad de su transformación, de un antiguo a un nuevo régimen: lo que supone la búsqueda de otros horizontes de sentido para engendrar formas plurales de habitabilidad en un momento francamente complejo y problemático, sin garantías. Para una introducción, véase Latour, B. (2017). Cara a cara con el planeta. Una nueva mirada sobre el cambio climático alejada de las posiciones apocalípticas. Siglo XXI.

[4] Para una mirada atenta a la pluralidad elemental de prácticas humanas y no humanas, o a la paradoja escalar de las múltiples configuraciones espaciales, corporales, temporales, histórico-culturales de nuestra omnipresente relación con el sol y la disipación de sus rayos o lo que pudiéramos llamar “solaridades” –– desde las formas infraestructurales vinculadas a la transición energética fotovoltaica a aquellas formas relacionadas con la catástrofe antropógena de la carbonificación de la atmósfera (donde el sol aparece como “the source of all withering and desiccation, a maker of monstrous heat”, p.18), por no olvidar de la centralidad planetaria de la fotosíntesis o los ciclos diurnos, o de su efecto en la producción de energías fósiles, por no hablar de nuestros sistemas de percepción visual –– véase la compilación de Howe, C., Diamanti, J., & Moore, A. (Eds.). (2023). Solarities: Elemental Encounters and Refractions. punctum books.

[5] El intento más detallado de restituir la centralidad de la sombra del que tengo conocimiento es el de Casati, R. (2003). Shadows. Unlocking their secrets from Plato to our time. Vintage Books.

[6] Martin, A. J. (2017). The Evolution Underground: Burrows, Bunkers, and the Marvelous Subterranean World Beneath our Feet. Pegasus Books.

[7] Coccia, E. (2021). El jardín del mundo, CENDEAC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxTQjBwuZRA&t=60s

[8]Albert, B., Halle, F., & Mancuso, S. (2019). Trees. Thames & Hudson; Coccia, E. (2017). La vida de las plantas: Una metafísica de la mixtura. Tipos Infames; Coccia, E. (2021). Metamorfosis. La fascinante continuidad de la vida. Siruela; Leonardi, C., & Stagi, F. (2022). La arquitectura de los árboles. Santa & Cole; Mattern, S. (2021). Tree Thinking. Places Journal, https://doi.org/10.22269/210921

[9] Como, por ejemplo, este concurso de prototipado del Ajuntament de Barcelona: https://bithabitat.barcelona/es/proyectos/sombra/

[10] Kite, S. (2017: 5). Shadow-makers: A cultural history of shadows in architecture. Bloomsbury Academic.

[11] Ludovico, M., Attilio, P. & Ettore, V. (Eds.) (2009). The Mediterranean Medina. Gangemi Editore.

[12] Turner, C. (Ed.) (2024). Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence. V&A Publishing.

[13] Kallipoliti, L. (2024). Histories of Ecological Design: An Unfinished Cyclopedia. Actar.

[14] Latour, B., & Weibel, P. (Eds.). (2020). Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth. ZKM / MIT Press

[15] Latour, B. (2019). Dónde aterrizar. Cómo orientarse en política. Taurus; Latour, B. (2021). ¿Dónde estoy? Una guía para habitar el planeta. Taurus.

[16] Horvath, T. (2009). The Discipline of Shadows. Conjunctions, 53, 293-311.

[17] Bauch, N., & Scott, E. E. (2012). The Los Angeles Urban Rangers: Actualizing Geographic Thought. Cultural Geographies, 19(3), 401-409; Kanouse, S. (2015). Critical Day Trips: Tourism and Land-Based Practice. In E. E. Scott & K. Swenson (2015). Critical landscapes: Art, space, politics (pp. 43-56). University of California Press.

[18] Gabinete de Crisis de Ficciones Políticas: https://www.gabinetedecrisis.es/

[19] Hepach, M.G. & Lüder, C. (2023). Sensing Weather and Climate: Phenomenological and Ethnographic Approaches. Environment and Planning F 2 (3): 350–68.

[20] Aït-Touati, F., Arènes, A., & Grégoire, A. (2019). Terra Forma: Manuel de cartographies potentielles. Éditions B42.

[21] Calvillo, N. (2023). Aeropolis: Queering Air in Toxicpolluted Worlds. Columbia Books on Architecture and the City; Fressoz, J.-B., & Locher, F. (2024). Chaos in the Heavens: The Forgotten History of Climate Change. Verso Books; Hsu, H. L. (2024). Air Conditioning. Bloomsbury; Parikka, J., & Dragona, D. (Eds.). (2024). Palabras de tiempo y del clima: Un glosario. Bartlebooth; Starosielski, N. (2021). Media Hot & Cold. Duke University Press.

[22] De la misma manera que los desiertos tampoco están vacíos, representación colonial comúnmente asociada a la justificación de formas de explotación salvaje de tierras áridas: Henni, S. (Ed.) (2022). Deserts Are Not Empty. Columbia Books on Architecture and the City

[23] Glissant, É. (2017). Por la opacidad. En Poéticas de la relación (pp.219-224). Universidad Nacional de Quilmes.

[24] Gissen, D. (2022). Disabling Environments. In The Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes Beyond Access (pp. 95-114). Minnesota University Press.

[25] Keller, R. C. (2015). Fatal Isolation: The Devastating Paris Heat Wave of 2003. University of Chicago Press; Macktoom, S., Anwar, N.H., & Cross, J. (2023). Hot climates in urban South Asia: Negotiating the right to and the politics of shade at the everyday scale in Karachi. Urban Studies, https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231195204

[26] Bloch, S. (2019). Shade: An Urban Design Mandate. Places Journal, https://doi.org/10.22269/190423; Macktoom, S., Anwar, N. H., & Cross, J. (2023). Hot climates in urban South Asia: Negotiating the right to and the politics of shade at the everyday scale in Karachi. Urban Studies, https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231195204

[27] Para un ejemplo interesante, véase Boserman, C. (2023). Dibujos solares: Los caballos de espinacas Sobre antotipias y afectividad ambiental / Solar Drawings: On anthotypies and environmental affectivity. Re-visiones, 13. http://www.re-visiones.net/index.php/RE-VISIONES/article/view/529

[28] En el rico sentido etológico explorado por Despret, V. (2022). Habitar como un pájaro: Modos de hacer y de pensar los territorios. Cactus. Una propuesta que rompe con la idea del territorio como algo que pueda explicarse bien en términos funcionales y económicos o en términos de propiedad, posesión y recursos explotables, reivindicando más bien la necesidad de describirlo desde las múltiples prácticas del habitar que lo constituyen y las artes de la convivencia que hacen posible.

Esta idea es desarrollada por Latour, B. (2021: 90). ¿Dónde estoy? Una guía para habitar el planeta. Taurus, para proponer una cartografía de los territorios diferente de las ideas de “sangre y suelo” que han fundamentado los tradicionalismos y nacionalismos europeos. Esto es crucial, en sus palabras, para orientarse en el Nuevo Régimen Climático, que requiere comprender de “dónde vivimos” a la vez que “de qué vivimos” listando nuestras afiliaciones.

[29] Department of Umbrology: https://umbrology.org/