[EN]

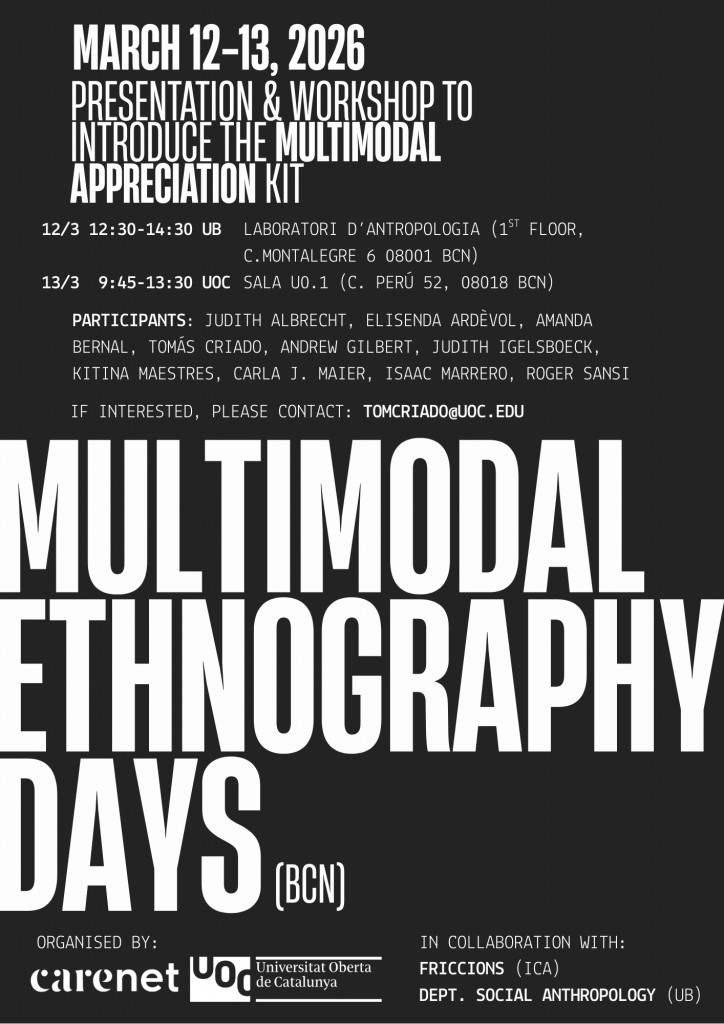

On March 12th and 13th, the Berlin colleagues with whom I have developed the Multimodal Appreciation kit will be visiting Barcelona: https://www2.hu-berlin.de/multimodalappreciation/kit/ (a toolkit for evaluating multimodal ethnographic research).

We have organized a two-part seminar: the first session will be held at UB on the 12th (more disciplinary), and the second at UOC on the 13th, focusing on interdisciplinary forms of multimodal ethnographic research.

You can find all the details at this link: https://symposium.uoc.edu/go/multimodalethnographydays (click here to download the program as a PDF)

I would greatly appreciate any help with spreading the word!

[ES]

Los próximos 12 y 13 de marzo visitarán Barcelona mis colegas de Berlín con quienes hemos desarrollado el kit Multimodal Appreciation: https://www2.hu-berlin.de/multimodalappreciation/kit/ (un kit para la evaluación de la investigación etnográfica multimodal).

Hemos organizado un seminario (que se impartirá en inglés) con dos partes: una en la UB el día 12 (más disciplinaria) y otra el día 13 en la UOC, más centrada en las formas interdisciplinarias de investigación etnográfica multimodal.

Me gustaría mucho invitaros a asistir. Tenéis toda la información en este enlace: https://symposium.uoc.edu/go/multimodalethnographydays (clicar aquí para descargar programa en PDF)

¡Agradecería cualquier ayuda con la difusión!

[CAT]

Els propers 12 i 13 de març visitaran Barcelona els meus col·legues de Berlín amb qui hem desenvolupat el kit Multimodal Appreciation: https://www2.hu-berlin.de/multimodalappreciation/kit/ (un kit per a l’avaluació de la recerca etnogràfica multimodal).

Hem organitzat un seminari (que es farà en anglès) amb dues parts: una a la UB el dia 12 (més disciplinària) i una altra el dia 13 a la UOC, més centrada en les formes interdisciplinàries de recerca etnogràfica multimodal.

Teniu tota la informació en aquest enllaç: https://symposium.uoc.edu/go/multimodalethnographydays (cliqueu aquí per descarregar una versió en PDF del programa).

Agrairia qualsevol ajuda amb la difusió!