Text for a short video intervention in the Homage: In conversation with Bruno Latour event, jointly organised last January 16, 2023 by the Stadtlabor for Multimodal Anthropology & the Laboratory: Anthropology of Environment | Human Relations at the Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (my former institution).

It’s a great pleasure for me to be able to join you all in celebrating one of the figures who has been accompanying me for the last 20 years of my life. I can even say that Bruno Latour is probably one of the main reasons why I became a researcher.

I suppose many of you know Bruno Latour as an anthropologist of science and technology, from his earlier laboratory studies to the works on different kinds of techniques. Some of you might read him as a philosopher of mediation and translation.

But it is as a multimodal thinker that I would like to refer to him. And not only because of his interest in the many modes of existence (multi-modal), but because of his collective explorations of different media forms (multi-media) to articulate them (in a plurality of epistemic ways).

He has notably been exploring different registers of writing, of which two main works stand out:

- Paris Ville Invisible: For those studying or interested in studying urban phenomena this is a masterpiece. An essay of photographic social theory, where Latour and Emilie Hermant explore how Paris, the “City of Lights”, cannot exist were it not for a million mediation devices and gadgets circulating to render it graspable, knowable, visible.

- But also, Aramis, or The Love of Technology: A study in the form of a detective novel, following the comings and goings, the trajectories of nonexistence and existence of a transportation system in Paris. This one is an incredible food for thought, not only because of its form, but also because neglected more than human agents are granted a specific and concrete voice in the telling, perhaps in connection with the work of writer Richard Powers (I’m thinking here of Galatea 2.2, on machine learning and a computer developing a self; The Overstory, on people dealing with the deep time of trees; or my favourite, The Echomaker, where some sort of Oliver Sacks is confronted with neurological patients finally speaking back at him, disputing his use of them to write books about otherworld minds).

Beyond these experiments in writing, which Latour has been always been undertaking as someone interested in semiotics, I think there are three other passions of his that I believe are of great inspiration for anyone interested in multimodal explorations.

First, his long-time interest in diagrams, which together with Frédérique Aït-Touati and Alexandra Arènes they have been more recently developing even further (check their marvellous Terra Forma). Rather than representational devices aiming to simplify, their diagrams are tools for concept-making and abstraction, enabling to grapple with complex operations of thought: such as, the distinction between purification and translation, the drama of technical scripts, which planet we might be on, or what it might mean to come back down to Earth. Second, Latour has been invested, also together with Aït-Touati, in unfolding dramaturgical experiments. Their most recent works (the Theater of Negotiations discussed in the last chapter of Facing Gaia, or the beautiful Trilogie Terrestre) explore the mise-en-scène of the intrusions of Gaia, making them knowable and politically graspable.

But it is perhaps as a co-curator of exhibitions—or Gedankenaustellungen (thought exhibitions, a wordplay with the German word for thought experiments, as Latour and Peter Weibel called them)—that this multimodal feature is perhaps better apprehensible. Mostly in Making Things Public, which has been a tremendous inspiration for many of us: a whole exhibition exploring the Dingpolitik, that is, the new political formations, or new political architectures that should be made relevant to deal with the multi-scalar assemblies of humans and nonhumans populating our everyday life. But also in the experimentation with protocols to Reset Modernity!. More recently, after publishing Facing Gaia and Down to Earth, he also co-curated the exhibition Critical Zones, which mostly had an online life do to the pandemic, but has perhaps the most beautiful catalogue of them all.

In Critical Zones, as in all his recent work, he has been calling for the arts to step up in the ecological mutation we’re undergoing. This is perhaps nowhere more clearly stated than in his recently published On the Emergence of an Ecological Class: A Memo, together with Nicolaj Schultz. In this work, they call for the arts to have a very peculiar role in composing, equipping this new ecological class. And they do not just refer to politically-minded art, conveying aesthetically ready-made political aspirations, but rather to more speculative, art-based forms of inquiry, exploring the descriptive and affective registers to develop new sensitivities, new aesthetics that should be made relevant to compose such an ecological class. This was something he thoroughly explored, collectively, in the study program he directed at Sciences Po: The School of Political Arts.

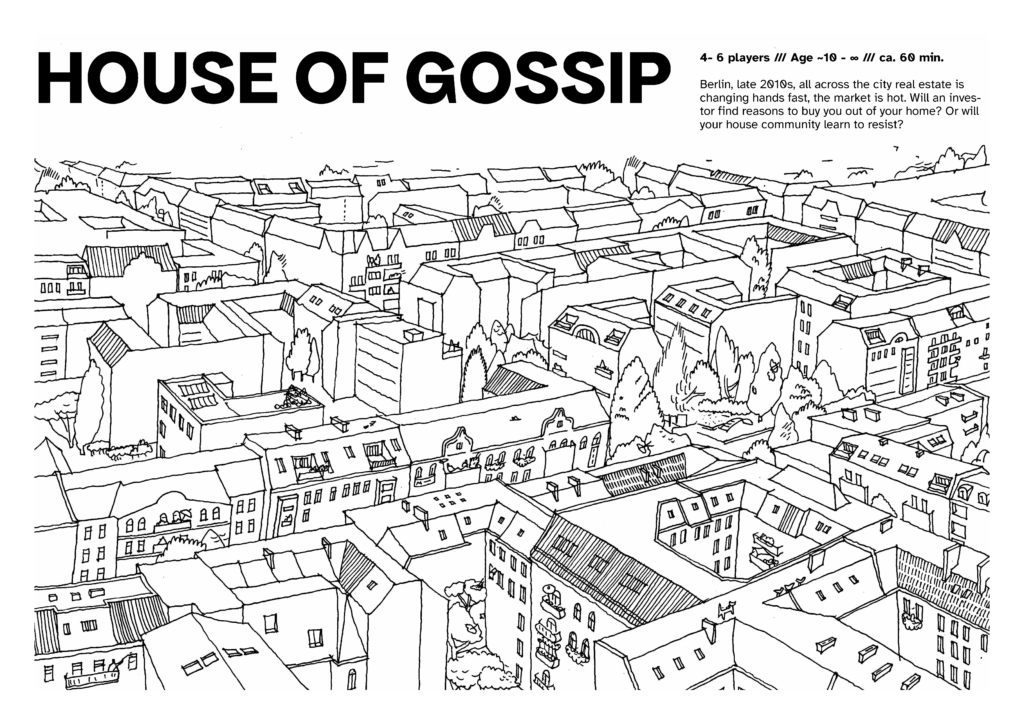

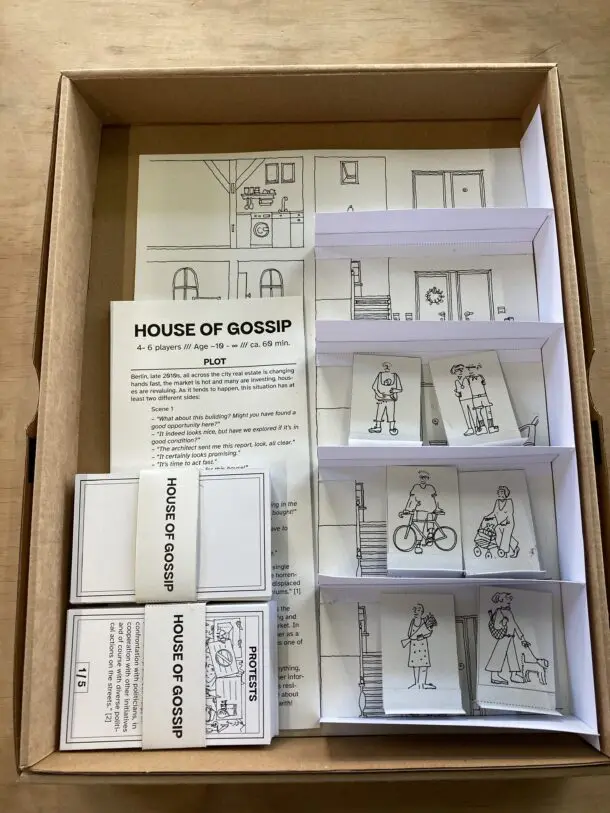

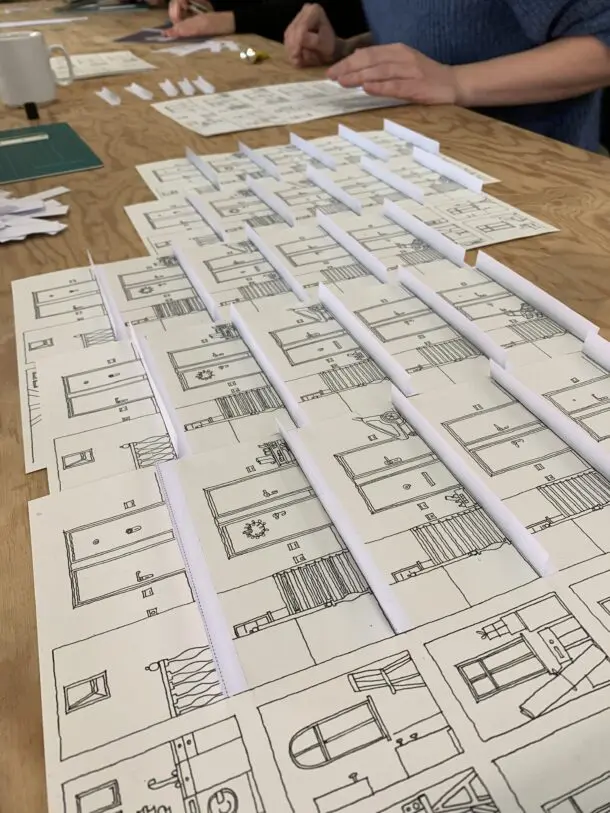

For all of these reasons the work of Latour has been of tremendous inspiration for the recent explorations of the Stadtlabor for multimodal anthropology, developing games and other sorts of public devices. To exemplify with our research through and with games, allow me to talk a bit in closing about House of Gossip and, more recently, Waste What?, the two games we’ve prototyped so far.

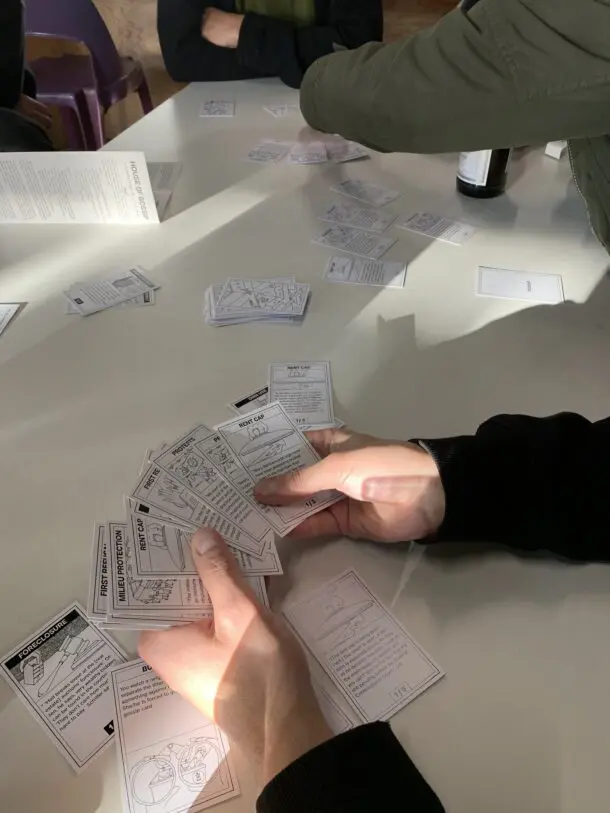

Using games as media we sought to explore alternative scenographies and devices of fieldwork, where games could act as peculiar multi-sensory assemblies where we could start doing highly-specific forms of research on urban phenomena, also eliciting fieldwork materials to engage in composing diverse kinds of publics.

In House of Gossip we explored, materializing a stairway, how a community of residents could come together: immersing themselves in thinking, or remembering the predicaments of dealing with the peculiar real estate and housing market assemblages creating great troubles in contemporary urban arenas (a true crisis of habitability!), such as in Berlin and many other big European cities.

In Waste What? we have been trying to abstract and reenact—by means of a loop-based game mechanic—the attempts of different institutional and activist initiatives of the circular economy from Berlin, particularly in connection with the Haus der Materialisierung. These are trying to explore, different attempts at closing the circle: that is, thwarting and blocking the throwaway culture of our consumerist societies, engendering new forms of habitability, of inhabiting Gaia.

But these are far from the only ways in which Latour has inspired many of us interested in doing multimodal urban research and public work. Be it at the Stadtlabor, or elsewhere (in my case now in Barcelona), I’m well aware all of us will continue to think and work with Latour’s multimodal impetus for many years to come.

May this be our homage to such a joyous multimodal thinker!