Together with Ignacio Farías we are convening the workshop Towards a multimodal urban anthropology for the upcoming biannual conference of the German Association of Social and Cultural Anthropology (DGSKA-Tagung 2021, “Worlds, Zones, Atmospheres. Seismographies of the Anthropocene”) that will take place (online) September 27-30, 2021 at the University of Bremen.

Our session is scheduled to take place 28.9.2021, 13:30–15:00 (CET) through the online platform of the conference | see programme here.

Frame of the workshop

More-than-human approaches in urban anthropology have convincingly contributed to rethinking the plurality of modes of knowledge, the assemblages and the kinds of actors that constitute our cities. But what do these conceptual interventions do to our ethnographic modes of inquiry? This workshop starts from the assumption that beyond a change in conceptual repertoires, decentering the all-too-human object of urban anthropology might require a multimodal transformation of our ethnographic practices, in at least two ways: Firstly, since the ‘observation’ of more-than-human entanglements requires more than taking part in social situations, what are the conditions in which we could appreciate and learn to be affected, attuned and concerned with a wide variety of phenomena and processes, ranging from atmospheric and ecological to multi-species and/or socio-technical? How would our practices of note-taking and field-working be affected? In contexts where fieldwork becomes an active co-production of situations, we invite contributions reflecting on multimodal transformations of fieldnotes, practices of rapport / friendship / interlocution and correspondence. Secondly, to the extent that these often-experimental collaborations involve more-than-textual devices for ethnographic description and conceptualization, we would like to explore the anthropological potentials of current displacements of the media and modalities of ethnographic accounts. In a context where collaborations with art and design are becoming a common practice, we particularly welcome contributions that reflect on the intervention these devices entail for the project of urban anthropology.

Participants & abstracts

- Graphic Ethnography and Experiments in Urban Anthropology (Andrew Gilbert, University of Toronto Mississauga; Larisa Kurtovic, Univ. of Ottawa)

In this presentation, we draw upon our graphic ethnography project to explore the affordances of sequential art for urban anthropology. Our research investigates an unprecedented victory by industrial workers in the northern Bosnian city of Tuzla, who occupied and preserved their privatized and bankrupted factory and were able to restart production. We propose that the graphic medium offers unique ethnographic potential for capturing and communicating the openly experimental and collaborative nature of the workers struggle, offering important insights for an urban anthropology “understood as operating within an open system, as an open system, and as the study and production of open systems” (Fortun 2003). In particular, we explore graphic ethnography’s capacity to materialize and render tangible a broad urban sensorium, to evoke how the social multiplicities of cities can be turned into a political resource, and to harness the imagination and participation of readers in ways that keeps ethnography as inventive and open-ended as the urban worlds that it evokes.

- Learning from outside: grasping and representing multiplicities. The case of pedestrianized Times Square (Santiago Orrego, HU Berlin)

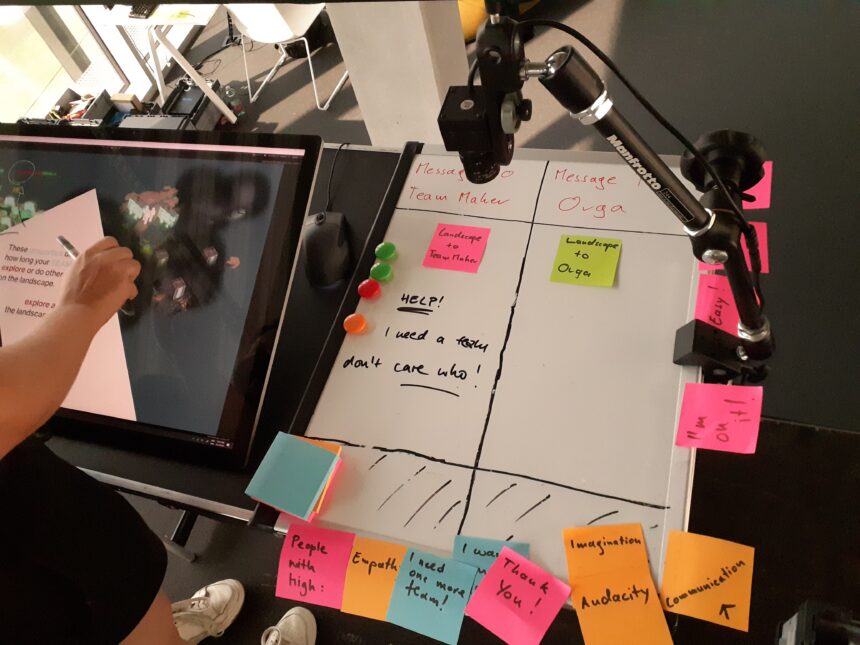

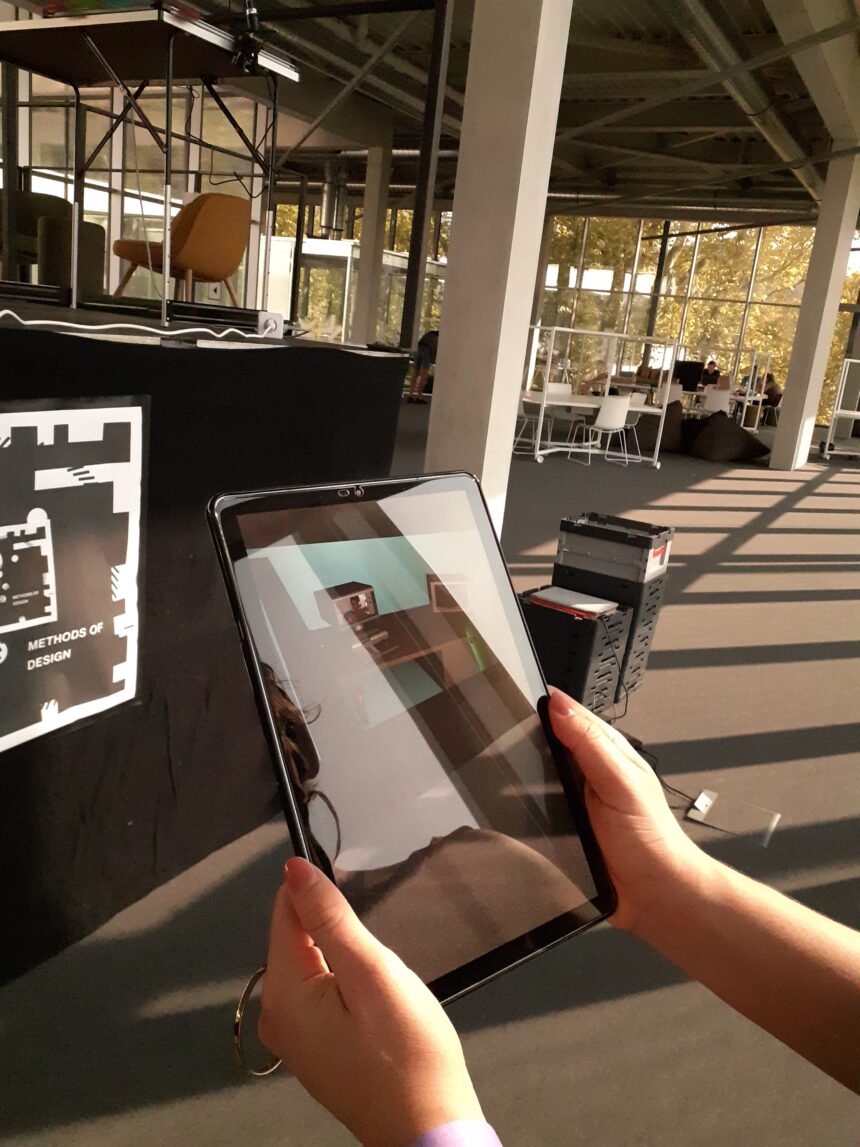

This talk is divided into two parts. The first one presents the highlights of a multi-situated and multimodal ethnography of Times Square in New York City and its processes of pedestrianization from 2009 to 2017. But more than just telling the story of how that location was assembled, the idea was to try to translate the particularities of a multiple spatiality, as well as the resources and situations involved in its production, somehow, into epistemological devices and multimodal artifacts that could enrich the way we make ethnography of public spaces. The intention of experimenting with multimodal methods was to design strategies, as well as artifacts, for better capturing and representing the convulse and the effervescent world outside. The second part of the talk will focus on some of those epistemological devices and multimodal artifacts by discussing how they were constructed, the rationality behind them, their uses, and scopes. The way for enacting all those matters will be presenting the methodological strategy carried out along this whole ethnographic work, and that can be described as a process of “learning from” a specific location, pedestrianized Times Square.

- Archival entanglements: Multimodal research, teaching, learning in urban anthropology (Aylin Tschoepe, University of Basel)

As a site of selective public or private memory, a collection of evidence in material and immaterial form shaped by various power dynamics, and a metaphor for holding data, the archive is central to the mediated production and understanding of archival bodies as agents and mnemonic devices. Archives offer a lens to grapple with questions of temporality, materiality, technological possibilities, and accessibility to different ways of knowing. I understand bodies and spaces as archives, not least through cultural practices of memorizing and forgetting, categorization, valuation and visibility. I am drawn to the archive in its complexity of objecthood and agency and focus on four main aspects: first, the archive as artefact holds particular knowledges and memories in the context of power and valuation, and can consist of various media and formats from material to digital. Second, the archive can be inscribed onto human and non-human actors. Third, as storages of data, archives may be part of a network with archival instruments that inscribe experiences and practices such as those of a cultural, social, performative, sensory, or aesthetic kind. Fourth, the archive is an actor itself, and it can contain further archival bodies that are also “quasi-objects” (Latour 2005). As actors, archives are also witnesses, equipped with transformative powers toward shaping the future of larger temporal and spatial networks in which archives operate and are entangled.

- Doing urban anthropology with a dog. Reflections upon ethnography and knowledge production in context of a more-than-human research entanglement (Elisabeth Luggauer, University Graz/University Würzburg)

This paper reflects upon multimodal ethnographic modes of being in a field of urban contact zones (Haraway 2008) or urban assemblages (Farias 2011) between humans and street dogs in Podgorica (Montenegro) as a multispecies research entanglement of a human and the dog Ferdinand. It points out how through the grounding ethnographic technique of jointly claiming urban space as a „humandog collective“ (Hodgetts 2018) 1. the presence of the mixed-breed dog reveals urban discourses and politics about street dogs and owned dogs as well as about cleanliness and dirt, 2. Ferdinand’s spatial practices make contact zones/assemblages between humans and street dogs recognizable for the human researcher and therefore open up concrete research settings for deeper investigation, and 3. our presence as a multispecies research team has also turned this project into a contact zone between different knowledges and discourses on human-nonhuman order policies in urban spaces embedded in different cultural and political contexts.

- Discussant: Indrawan Prabaharyaka (HU Berlin)

Questions for our joint exploration

The question we would like to approach collectively in our workshop is how do particular multimedia/multimodal devices enable or hinder particular descriptions, conceptual understandings or ways of remaking what the urban is or could be. This not only means what features of the urban they enable or make more difficult to do research upon, but also whether our understandings of the urban remain the same after inquiring multimodally. Put differently, what kind of an urban anthropology emerges out of these multimodal engagements? That is, what would a multimodal urban anthropology be?

With these questions in mind, when creating the sequence of presentations for the session we have paid special attention to the particular ‘devices’ (be they field devices, representational devices, or both) there are stake, with the intention to discuss the multimedia layers that have paved the way for a question around the multimodal in anthropology. Hence, there is a transition from the visual/graphic to the digital, then to more material aspects like the archive and the multi-sensory as well as the collaborative (perhaps a genealogy in which the problem of multimodality presented itself in recent anthropological scholarly work?). But whereas the first two (Gilbert & Kurtovic + Orrego) emphasise visual means of representation (comic/graphic novel and exhibition artefacts), the last two (Tschoepe + Luggauer) discuss multimodal strategies of research in the field (through archives, and in the company of dogs). Perhaps this might enable a discussion on when and where multimodality happens, and how this affects the research process.