[CAT] Benvolgudes / benvolguts

Us convidem a la presentació del Departament d’Umbrologia, que tindrà lloc el proper 26 gener 2026 a les 10h, a la Sala d’actes de Fabra i Coats: Fàbrica de Creació (C. Sant Adrià 20, Barcelona)

El Departament d’Umbrologia és un projecte transdisciplinari finançat per la Fundació Daniel i Nina Carasso, a la seva convocatòria «Compondre sabers per imaginar i construir futurs sostenibles». Aquest projecte articula quatre socis de la ciutat de Barcelona en la cruïlla de les humanitats, l’arquitectura, les arts i les ciències ambientals: els grups CareNet & DARTS (UOC), Arquitectura de Contacte, Nusos Coop i Laboratorio de Pensamiento Lúdico

Volem prototipar el Departament d’Umbrologia com una institució especulativa per a l’estudi i la intervenció de la vida urbana de les ombres a partir d’una sèrie de tallers de co-creació, col·laboratius i oberts (en el primer any), que desembocaran en un Festival de les Ombres al 2027.

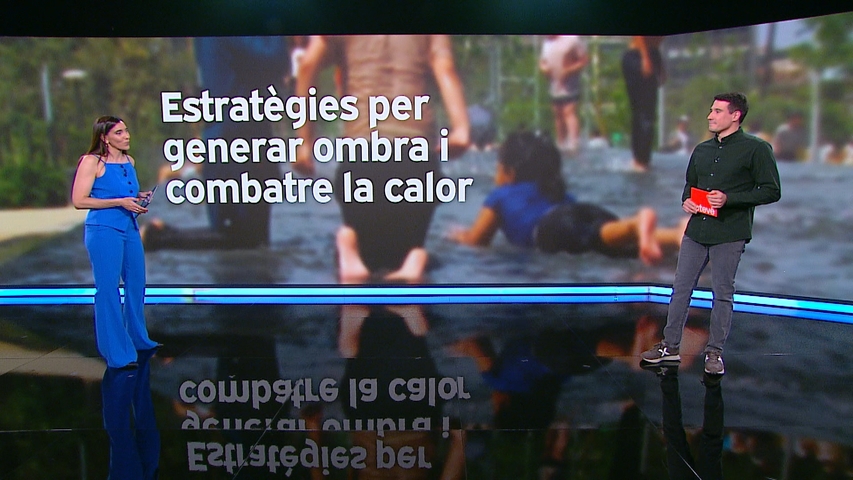

El projecte busca revitalitzar sabers intergeneracionals, interculturals i interespècie, així com estètiques de l’ombra per afrontar comunitàriament les transformacions urbanes que el canvi climàtic suposa. Amb les nostres activitats volem reclamar la sobirania popular de les ombres i la protecció que aquestes ofereixen.

Podeu registrar-vos i incloure les vostres preferències alimentàries en el següent formulari: https://forms.gle/TWbKjEV7RsMcsTN18 (abans del 21 de gener)

Agrairem la vostra ajuda enviant aquesta invitació a totes les persones potencialment interessades

Cordialment,

El Departament d’Umbrologia: un projecte dels grups CareNet & DARTS (UOC), Arquitectura de Contacte, Nusos Coop i Laboratorio de Pensamiento Lúdico

En col·laboració amb Fabra i Coats: Fàbrica de Creació

+ info: https://umbrology.org/carasso-2025-2027/

***

[ESP] Hola a todes,

Os invitanos a la presentación del Departamento de Umbrología, que tendrá lugar el próximo 26 de enero de 2026 a las 10 en el Salón de actos de Fabra i Coats: Fàbrica de Creació (C. Sant Adrià 20, Barcelona)

El Departamento de Umbrología es un proyecto transdisciplinario financiado por la Fundación Daniel y Nina Carasso, en su convocatoria «Componer saberes para imaginar y construir futuros sostenibles». Este proyecto articula a cuatro socios de la ciudad de Barcelona en el cruce de las humanidades, la arquitectura, las artes y las ciencias ambientales: los grupos CareNet & DARTS (UOC), Arquitectura de Contacte, Nusos Coop y Laboratorio de Pensamiento Lúdico

Queremos prototipar el Departamento de Umbrología como una institución especulativa para el estudio y la intervención de la vida urbana de las sombras, a partir de una serie de talleres de co-creación, colaborativos y abiertos (en el primer año), que desembocarán en un Festival de las Sombras en 2027.

El proyecto busca revitalizar saberes intergeneracionales, interculturales e interespecie, así como estéticas de la sombra para afrontar comunitariamente las transformaciones urbanas que el cambio climático supone. Con nuestras actividades queremos reclamar la soberanía popular de las sombras y la protección que éstas ofrecen.

Podéis registraros e incluir vuestras preferencias alimentarias en el siguiente formulario:https://forms.gle/TWbKjEV7RsMcsTN18 (antes del 21 de enero)

Agradeceríamos vuestra ayuda enviando esta invitación a cualquier persona potencialmente interesada.

Cordialmente,

El Departamento de Umbrología: un proyecto de los grupos CareNet & DARTS (UOC), Arquitectura de Contacte, Nusos Coop y Laboratorio de Pensamiento Lúdico

En colaboración con Fabra i Coats: Fàbrica de Creació

+ información:https://umbrology.org/carasso-2025-2027/